Diagnosing Critically Ill Newborns: The Evolution of Testing and the Promise of Rapid Whole Genome Sequencing

The prenatal ultrasound revealed enlarged echogenic, or unusually bright, kidneys, polydactyly, and club feet that curved inward. The development of the fetus at 32 weeks of gestation already indicated the presence of a genetic disorder. By the day after birth, the infant was enrolled in a research study to rapidly diagnose newborns with genetic disorders. By day six, the parents and their new baby had received an answer: Bardet-Biedl syndrome.

Rapid whole genome sequencing (rWGS), a test that analyzes the entire genome for pathogenic variants in just a few days, made it possible for this family to receive a diagnosis in less than a week.

“With a traditional testing modality, it may have taken years for someone to realize the clinical picture matched Bardet-Biedl syndrome,” said Hunter Best, PhD, FACMG, head of the Molecular Division at ARUP and medical director of Molecular Genetics and Genomics. “The patient would probably have been to literally dozens of doctor visits without receiving a diagnosis.”

Bardet-Biedl syndrome is a rare genetic disorder characterized by excessive childhood weight, poor eyesight, kidney dysfunction, extra fingers or toes, and impairments in thinking, learning, and speaking. The symptoms of Bardet-Biedl syndrome develop slowly over time, making timely diagnosis difficult.

“The symptomology that is the hallmark of Bardet-Biedl syndrome was not present in the infant,” Best said. “This means that rWGS is providing a diagnosis before the full clinical picture has evolved.”

By identifying genetic disorders within a few days of birth, rWGS better informs management strategies and enables specialist intervention. In some cases, timely diagnosis may even prevent permanent harm or mortality.

“It may sound like a small thing to refer these patients to a specialist, but early specialist intervention makes a huge impact in the outcome of these patients,” Best said.

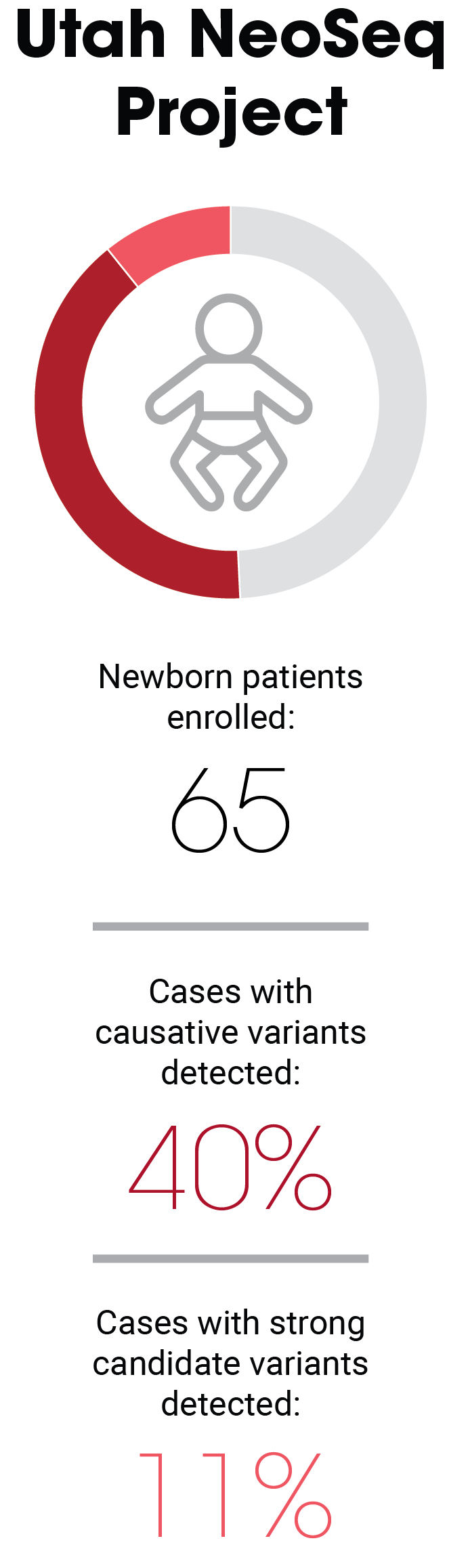

This patient was one of 65 newborns who were enrolled in the Utah NeoSeq Project, a collaborative research effort to evaluate the clinical value of rWGS for critically ill infants being treated in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at the University of Utah Hospital. ARUP Laboratories performed testing and data analysis for each of the patients enrolled in NeoSeq, which launched in February 2020 and concluded in May 2023.

Of the 65 infants enrolled during that period, rWGS identified causative variants in 40% of the patients and strong candidates in an additional 11% of the patients. To compare the rWGS results with those of traditional testing modalities, standard-of-care testing was also ordered. In the infant with Bardet-Biedl syndrome, standard tests didn’t yield results until two weeks after the results of rWGS testing were in.

“When we say rapid, we mean rapid,” Best said. “It’s not rapid with a disclaimer; it’s rapid. We have spent years optimizing our workflow to guarantee our published turnaround times.” rWGS yields results in just three to seven days.

For critically ill infants in the NICU, rapid diagnosis is essential to initiate treatment in time or facilitate management strategies.

Best has led the development of whole genome sequencing at ARUP, in collaboration with ARUP’s Genetics and Genomics teams. The whole genome sequencing assays now include copy number variants (CNVs), mitochondrial sequence variants, and SMN1 deletions to identify spinal muscular atrophy.

ARUP’s teams have extensive experience performing and interpreting genomic sequencing. They were early adopters of the test method used to sequence genomes, known as massively parallel or next generation sequencing, and participants in early research initiatives such as the Utah NeoSeq Project.

“There are many different types of large copy number variant-type abnormalities that we can detect with the improved assays,” said Patti Krautscheid, MS, LCGC, genetic counselor and supervisor of Genetic Counseling Services at ARUP. “Adding CNV detection makes the tests a one-stop shop for great first-line diagnostic tests.”

Clinical evidence in support of genomic sequencing as a first-tier testing strategy is mounting. In July 2025, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published updated recommendations for the evaluation of children with global developmental delay (GDD)/intellectual disability (ID). The recommendations include using exome or genome sequencing as an initial, or first-tier, test for diagnosing GDD/ID. This follows recommendations that were already established by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC).

As a result of these guideline recommendations, several major insurance companies and state Medicaid programs have expanded coverage for rWGS, especially for critically ill newborns who are being treated in the NICU. As of September 2025, 17 state Medicaid programs cover rWGS for critically ill children younger than 1 year, and an additional four states have introduced coverage policies that have not yet been enacted.

By sequencing the entire genome, rather than testing for variants in a targeted gene, a broader range of genetic disorders can be identified.

“Whole genome sequencing provides more data on coding and noncoding regions, increasing the diagnostic yield,” Best said. “This test should be considered as a first-line diagnostic test when an inherited disorder is suspected but the patient phenotype does not suggest any single disorder.”

Genomic sequencing produces an incredible amount of data. ARUP has built a custom analysis tool, NGS.web, to help filter the data, but relies on the expertise of the team’s medical directors and clinical variant scientists to interpret it.

“This testing is very complex, and it’s not directed at one single marker,” Best said. “We use limited artificial intelligence (AI) tools to filter the data, but we manually interpret variants 100% of the time, using the significant years of experience that our teams have. It’s not possible to replace that experience.”

Although ARUP’s genomic sequencing assays are currently only used to evaluate symptomatic patients with suspected inherited disorders, several studies and organizations are investigating the utility of rWGS as a general newborn screening tool.

While genomic sequencing is not yet as rapid as other newborn screening methods, it is an incredibly informative tool that has significant implications for diagnosing critically ill newborns.

“As genome sequencing becomes cheaper, it starts to become more feasible to utilize this technology to help drive healthcare decisions, even in healthy populations,” Best said. “Genomics can be harnessed to start directing personalized care.”